We look at the extraordinary life story of ‘the greatest American architect of all time’ and celebrate his continuing influence on buildings, interior design, furniture and, of course, lighting…

We look at the extraordinary life story of ‘the greatest American architect of all time’ and celebrate his continuing influence on buildings, interior design, furniture and, of course, lighting…

Frank Lloyd Wright was one of the towering figures of 20th century architecture but, like many of the great designers, he was very much a polymath and turned his talents to all sorts of things. His creative output spanned 70 years, embracing not only architecture and design (interiors, furniture and lighting) but writing and education too.

He had a lasting belief in ‘organic’ architecture – designing in harmony with human habitation and the natural environment, with recurring materials and signature motifs and ordering principles. Fallingwater, the Pennsylvania house he designed in 1935, is regarded by many as the finest example of American architecture and, in 1991, the American Institute of Architects recognised Lloyd Wright as “the greatest American architect of all time.”

And, as far as we know, he is the only architect to have been immortalised in a classic pop song.

Fallingwater, Pennsylvania (1935) – via Creative Commons

Fallingwater, Pennsylvania (1935) – via Creative Commons

So how did a man born into a poor, unhappy family, who left university early, and whose life was not without tragedy, reach such heights?

The early years

Frank Lloyd Wright was born in Ruchland Center, Wisconsin, in 1867, the son and first child of a former Baptist, later Unitarian, minister and music composer, William Cary Wright, and Anna Lloyd Jones, whose parents had emigrated from Wales.

There was little money and the marriage was unhappy. His parents separated when Frank was 14, eventually divorced, and Wright senior disappeared from his son’s life completely in 1885.

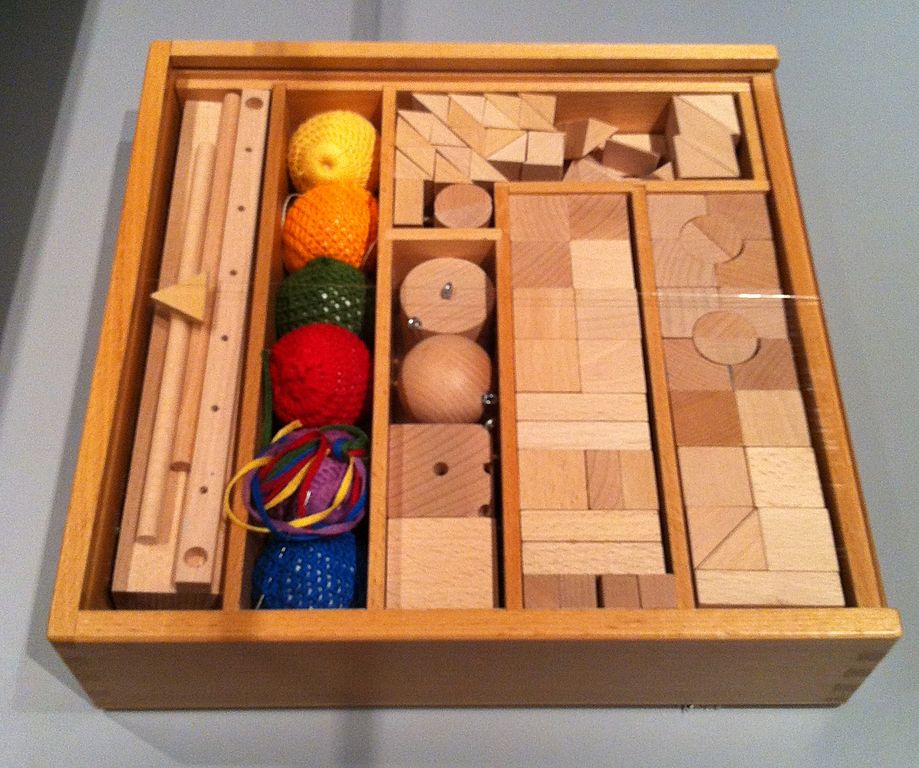

Despite the family difficulties, Anna, a trained teacher, always had a sense that that her firstborn would achieve great things and create great buildings. She bought Frank a set of Froebel Gifts when he was nine, and he played with them endlessly; these geometrically shaped blocks could be used to build complex two- and three-dimensional shapes and would inspire Frank throughout his life.

A reproduction set of Froebel Gifts – via Creative Commons

A reproduction set of Froebel Gifts – via Creative Commons

As he reached his teens, Frank decided he wanted to become an architect and he enrolled at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, where he studied civil engineering – but never graduated. He found work as a draughtsman in Chicago, much of which had been destroyed by fire in 1871 and was therefore ripe for redevelopment.

But work as a draughtsman for just $8 a week was never going to satisfy him and he soon moved on to a employment as an architectural designer. In 1888, he joined the Chicago firm of Adler & Sullivan, where co-founder, Louis Sullivan (the “father of modernism”) rapidly became a mentor – and another lifelong influence, although he stopped speaking to Wright for 12 years after discovering that his protégé had been working independently on private commissions.

The firm did not design or build houses, so Frank had worked in his spare time on nine houses, most of which can still be seen today. These early houses incorporated some of the design elements, such as geometric massing and bands of horizontal windows that would become a hallmark of his work.

Walter Gale House, Oak Park, Illinois (1893) – via creative commons

Walter Gale House, Oak Park, Illinois (1893) – via creative commons

Branching out

Interior, Robie House, Chicago, Illinois (1910) – via creative commons

Interior, Robie House, Chicago, Illinois (1910) – via creative commons

In 1893, Frank set up his own practice in downtown Chicago, working closely with a group of young architects, all inspired by the Arts and Crafts Movement, and Sullivan’s design philosophies, to form the Prairie School. His early commissions featured simple geometry and horizontal lines – inspired by ancient Mayan buildings – and Sullivan-inspired details, as well as more traditional designs for clients with conservative tastes.

At the same time, Frank, who had married Catherine (Kitty) Tobin in 1889, was father to a growing family (six in total) and decided to relocate his studio to his home in Oak Park, built when the couple married, for a better work-life balance. This move was critical in his development. It meant reconfiguring the layout and building the studio extension and it was here that he could experiment with innovative structures, including a hanging balcony.

Work on the Prairie Houses, on land around Chicago continued. They included the dramatic Robie House with its cantilevered roof and large open plan living and dining. There were major public works too, such as Oak Park’s Unity Temple, for his own local Unitarian community.

Interior, Unity Temple, Oak Park, Illinois (1908) – creative commons

Interior, Unity Temple, Oak Park, Illinois (1908) – creative commons

At the same time, Frank’s family private life was unravelling. In 1903, he had met and fallen in love with Mamah Borthwick Cheney, the wife of a client; the couple left their respective spouses and children and ran off to Italy. Back in the USA in 1910, Wright began work on their new home, called Taliesin in honour of his Welsh roots. But, just four years later, an appalling tragedy struck when a family servant set fire to the living quarters and then murdered seven people, including Mamah and her two children, as the property burned.

The Japanese influence

Entrance Hall and lobby, Imperial Hotel, Tokyo (1923) – recreated at Museum Meiji-mura. Photo by insho impression via creative commons

Even for those unfamiliar with many of Frank Lloyd Wright’s buildings, it is easy to spot his admiration for Japanese design, fuelled by the time he spent in the country from 1917-1922, and where he left a considerable architectural legacy. The Imperial Hotel in Tokyo, which was completed in 1923, had such strong foundations that it survived a major earthquake in the same year, and was almost unscathed. As much as Japanese design was a major influence on Wright, so Wright, in his turn, would become a major influence on Japanese architects.

But away from his work, Frank’s exceptionally turbulent private life continued to twist and turn. By the time he returned to the USA in 1922, his first wife Kitty had finally agreed to a divorce, and Wright married his then mistress, Miriam Noel. But this marriage lasted less than a year and, in 1927, also ended in divorce.

Meanwhile, Frank had met and was living at Taliesin with Olgivanna Hinzenburg, a disciple of the Armenian mystic guru Gurdjieff. But fate was not kind to this apparently cursed property: in 1925, fire struck again and the Taliesin bungalow in which they were living was destroyed, as was Frank’s precious collection of Japanese prints (which today would have been worth some $8 million).

However, this time he was more fortunate in his marriage, and Frank and Olgivanna’s union endured until his death in 1959. And despite Taliesin’s decidedly chequered history, Frank would rebuild the living quarters, which became Taliesin III, and he and Olgivanna set up The Fellowship, a kind of school combining the couple’s skills to enable students to learn about architecture while pursuing spiritual development.

Usonian houses and late works

Living room, Jacobs 1, Madison, Wisconsin (1937), Wright’s first Usonian house – via creative commons

Living room, Jacobs 1, Madison, Wisconsin (1937), Wright’s first Usonian house – via creative commons

In the 1930s, Frank worked on a suburban complex, Broadacre City, also known as Usonia. Usonian houses were a natural development of Prairie Houses, while taking account of sweeping changes in American domestic life with the disappearance of domestic servants. In 1937, he completed Fallingwater, built in a series of cantilevered balconies and terraces over a 30-foot waterfall, and which blended into and made the most of its natural surroundings.

Olgivanna’s bedroom, Taliesin West, Scottsdale, Arizona (1937) – via creative commons

At Scottsdale, Arizona, he built Taliesin West as a winter home and studio and, from 1943-1959, he was focused on the Solomon R Guggenheim Museum in New York City, generally regarded as his masterpiece.

Interior, Solomon R Guggenheim Museum, New York City (1943-1959) – via creative commons

Interior, Solomon R Guggenheim Museum, New York City (1943-1959) – via creative commons

It was also his final architectural legacy. On 9 April 1959 Frank died, following surgery, at the age of 91.

Interiors, furniture, lighting and decorative arts

Interior, Robie House, Chicago, Illinois (1910). Photo via creative commons.

Interior, Robie House, Chicago, Illinois (1910). Photo via creative commons.

Throughout his life, Frank Lloyd Wright drew on the influences that had always sustained him: Froebel Gifts, Louis Sullivan, and Japanese art, prints and buildings, to which we must add nature, in particular the shapes, forms, colours and patterns of plant life, and music, especially that of Beethoven.

Like Charles Rennie Mackintosh, Wright believed every element in a building should work as part of a unified whole. His early oak furniture and furnishings reflect the solidity and simplicity we associate with the Arts and Crafts movement, with straight lines and rectilinear forms.

Bedroom, Pope-Leighey House, Mount Vernon, Virginia (1940) – via creative commons

Bedroom, Pope-Leighey House, Mount Vernon, Virginia (1940) – via creative commons

Yet he was a pioneer of building materials such as precast concrete bricks and glass bricks. Design schemes often include murals and sculptures, and he used glass on a vast scale to make the most of natural light.

He was one of the first architects to design custom-made electric light fittings, including floor lamps and spherical glass lampshades. There were wall sconces too, made of leaded glass, oak and bronze, and recessed lighting, hidden in ceilings behind rice paper.

Frank Lloyd Wright’s studio, Oak Park, Illinois (1889 and 1898) – via creative commons

Frank Lloyd Wright’s studio, Oak Park, Illinois (1889 and 1898) – via creative commons

Lighting in the Frank Lloyd Wright style

Frank Lloyd Wright had a penchant for pendant lighting in interesting geometric shapes, both square and spherical.

Our Hunza chandelier is very Wrightish, consisting of 14 faces of prismatic glass in shallow pyramids, set in a solid brass frame. It’s complex, yet the visual effect is one of pleasing simplicity, ideal for hovering above a kitchen island or over a dining table...

Hunza chandelier

Hunza chandelier

There is nothing deceptive about our simple Carrington lantern: a glass pendant with antique brass framework, nothing more, nothing less, but full of impact.

Carrington lantern

Carrington lantern

Wright often used colour in lighting, and Pooky’s Cookie in Military Green (with stone interior) is a direct descendant of the pendant style seen Wright interiors. Hang it singly or in rows.

Cookie in Military Green (with stone interior)

Cookie in Military Green (with stone interior)

We mentioned Wright’s fondness for concrete as a material, and our larger Soprano is Pooky’s first venture into concrete lighting, with a shape that just works beautifully.

Soprano in concrete

Soprano in concrete

Finally, we have to include spheres: our regular Espere is a blown glass dome topped by a brass gallery. We have Esperes in various forms of glass, from clear to waffle, but the opaline form is perhaps the most Frank-like; it casts a subtle, dappled light.

Espere in opaline glass

Espere in opaline glass

Thank you, and so long, Frank Lloyd Wright…

If we have whetted your appetite for all things Frank Lloyd Wight, you can find out more about his life and work at the Frank Lloyd Wright Trust and the Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation.

Image top: Frank Lloyd Wright 1867-1959 – via creative commons

See also:

Great interior designers: Charles Rennie Macintosh

The History of Design in Table Lamps – Art Deco

Classic interior design styles and how to light them – Art Deco