From art nouveau to postmodernism, our blog series shows how the humble table lamp can help us to understand the whole history of design. In this post we look at the varied and multi-national styles of the 1950s and 1960s known collectively as ‘mid-century modernism’ – and why it's a tale of four cities...

As we saw in part 2 of this series, ‘modernism’ as an ethos emerged very early in the 20th Century, founded on the principle that the design of an object should be based upon its practical purpose (‘Form follows function’). Its immediate counter-movement, Art Deco, rejected the modernist emphasis on utility and mass production in favour of exquisite craftsmanship, expensive materials, glamour and luxury. But the exuberance of Art Deco – the first truly world-wide design movement - was brought to an abrupt end by the Second World War. The social and economic traumas inflicted on Europe in the 1940s effectively shut down the design utopias of France and the Netherlands (birthplaces of Art Deco and De Stijl respectively) and of course Italy and Germany.

After the War, labour and resources were at a premium, and were focused on the mountainous task of rebuilding a wrecked continent. But across the Atlantic, things were very different. The United States survived the war economically intact – indeed, it experienced a consumer boom, and in the 1950s it became the dominant global force in politics, economics and popular culture. Furthermore, a great many of the star designers of Europe – including from Germany’s Bauhaus – had emigrated to America during the 1930s, and they found that there was plenty of intellectual and commercial space in the new world in which they could flourish.

Eerio Saarinen’s Tulip lamp, for the Herman Miller company – a classic US mid-century modern design. Image credit

In the middle of the 20th Century, the epicentre of global design shifted from somewhere between Paris and Berlin to New York City. The story of ‘midcentury modernism’, then, can be told as the rise of American design and consumer culture, and how the old countries of Europe in turn responded to the new order. So for our purposes, mid-century modern design is a tale of four cities: New York, Copenhagen, Helsinki and Milan. And as ever, table lamps provide perfect illustrations...

New York

Eames and Saarinen's furniture at the MoMA's "Organic Design in Home Furnishings". Charles Eames: Furniture from the Design Collection, The Museum of Modern Art, New York, Drexler. Image credit.

The seeds of America’s domination of design in the 1950s and 60s were planted in 1941, when New York’s Museum of Modern Art (MOMA) held a design competition in association with Bloomingdale’s department store. It was titled ‘Organic Designs in Home Furnishing’ and the judges awarded the top prizes to furniture and items that moved well away from the formal geometry of the early modernism, and instead mimicked the flowing lines of the human body. The subsequent exhibition launched the careers of Charles Eames and the Finnish-born Eero Saarinen, who collaborated on the victorious Organic Chair design. They, along with other great names like Florence Knoll, Harry Bertoia, George Nelson and Ray Eames (Charles’ wife) came to dominate US design.

George Nelson's 'Half-Nelson' table lamp (1955) made from chrome-plated aluminium. The adjustable reflector enables the light to be angled. Image credit.

Like the original modernists, and unlike the Art Deco artisans, America’s mid-century pioneers designed for mass production, working in affordable materials like plywood, polyester, aluminium and plastics. Crucially, they also worked closely with manufacturers – the most important being Knoll International and Herman Miller – who supported their ideas and packaged and sold them to the growing consumer markets across the world. However, where they differed from the previous modernist movements is that they were unencumbered by rigid intellectual rules of geometrical form and functionalism. Inspiration came from culture and contemporary art (think the sculptures of Henry Moore) and the mid-century brand of American modernism was warmer, more human, less predictable and often very witty.

Mitchell Bobrick - Table light (1950) combines a ceramic base and a fibreglass reflector. Image credit.

Copenhagen

In the early development of modernism, Germany was the main hotbed of talent and ideas. The Nazi period put an end to that, though after the war the Bauhaus modernist theoretical tradition was revived in the Ulm School for Design, which brought products to market through companies such as Braun.

Poul Henningsen's PH table lamp (1927). Image credit.

Denmark, however, also had a history of outstanding modernist design - the godfather being Poul Henningsen, who developed a series of classic pieces in the 1920s including the famous PH table light (above) - and in the 1950s Copenhagen became a centre for the new form of organic modernist design.

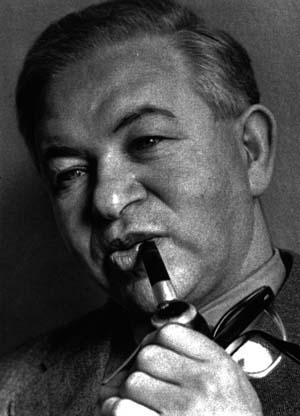

Arne Jacobsen

The apotheosis of Danish mid-century style was the SAS Royal Hotel, constructed between 1956 and 1960 and entirely designed inside and out (right down to the cutlery in the restaurant) by the visionary architect and designer Arne Jacobsen. He gave the world such enduring classics as the Swan and Egg chairs – not at all dissimilar to the 1940s work of Saarinen and Eames - as well as the iconic AJ table lamp.

Arne Jacobsen – AJ Table light for the SAS Royal Hotel, Copenhagen (1957) Image credit

Helsinki

Finland produced a series of extremely innovative designers in the 1950s and 60s. Most produced items for the Stockmann department store in Helsinki, and its sister company factory Stockmann-Orno. The Finnish mid-century design is characterized by simple, elegant forms – a good example being this 1954 table lamp by Lisa Johannson-Pape. Mold-blown and sandblasted glass made by the glassworks Iittala, the lamp is essentially a luminescent modernist sculpture.

Lisa Johansson-Pape - Table light (1954) Image credit

Indeed, so overt was the Helsinki design connection to modern art that another great Stockmann designer, Yki Nummi , actually called this minimalist masterpiece a ‘Modern Art table light’. Both base and shade are made from acrylic plastic – well ahead of its time in 1955.

Yki Nummi - 'Modern Art' table lamp (1955) Image credit

Milan

Achille Castiglioni and the famous modernist Arco lamp in 1960s Milan. Image credit.

But despite all these extraordinary designers, perhaps the most exciting work of the mid-century period came out of Italy. If the design of America was distinctively commercial and that of northern Europe distinctively intellectual, then Italian design was all about joyous creativity.

The enamelled-metal Model 534 table light (1951) by Gino Sarfatti. Image credit.

Prior to World War II, Italy had contributed little to industrial design, but the 1950s saw an explosion of creativity and style, produced by a number of factors including the country’s relatively late transition to industrialisation, the sudden success of its steel industry and the influence of US culture, especially Hollywood. Italy had no intellectual hang-ups about what design should be, leaving its designers – most of whom were based in Milan, home of the famous Triennale exhibition –free to imagine.

Taccia lamp (1962) by Achille and Pier Giacomo Castiglioni.Image credit

Milanese design was all about bringing manufacturing and design straight into culture and lifestyle – and soon Italian was a byword for cool across the world. Think Italian suits, Ferraris, Vespas, Olivetti typwriters, even espressos. Manufacturers like Kartell enthusiastically embraced man-made materials, and the Italians elevated plastic design to an art form. Take Vico Magristretti’s Dalu table light (1965) which achieves a modernist’s dream of making a single-object, single-material item, perfect for mass-production while remaining eminently stylish.

Vico Magristretti - Dalu table light (1965). Image credit.

But Italian mid-century design was above all incredibly varied. The Alfa table lamp (1959) by Sergio Mazza appears modernist in its striking, bold construction. But look a bit closer and you’ll see that as well as nickel-plated metal, it has marble in its base and crystal in its shade. Those are nostalgic materials, harking back to a pre-modern, bourgeois age. In fact, they are the just the sort of luxurious materials you’d expect to find in an Art Deco lamp.

Sergia Mazza - Alfa table lamp (1959). Image credit.

And so modernism’s counter-movement influences its revivalist movement, and round we go again. But if you think that’s confusing, just wait until the fifth and final instalment of this series, when we reach the last decades of the twentieth century and enter the age of postmodernism...

Pooky's midcentury modern-inspired Drax table light

See also: Arco lamps and artichokes: The Art of Midcentury Modern Lighting Design The History of Design in Table Lamps series: Part 1: Thomas Edison to Art Nouveau Part 2: The Birth of Modernism Part 3: Art Deco Part 4: Midcentury Modernism Part 5: Pop and Postmodernism