From art nouveau through modernism and art deco, our blog series shows how the domestic table lamp can help us to understand the whole history of design. In this final episode, we come right up to the present and look at that elusive concept, postmodernism...

The easiest way to comprehend the concept of ‘postmodernism’ is to be quite literal about it: it’s what came after modernism. And although ‘postmodern’ things take all sorts of forms across many disciplines, the uniting factor is that their designers have rejected the fundamental elements of modernist thinking. Modernism had one overriding principle: ‘form follows function’, meaning that the practical purpose of an object should determine its physical form. But it also made certain assumptions about quality and taste. In 1960s Germany, modernist industrial designers sought ‘good form’, a rational dogmatic approach where objects should aim for an ideal of functional excellence. Manufacturers in Italy were governed by a similar notion called ‘Bel Design’. The midcentury modernism of the 1950s and 1960s was driven by mass production catering to a new consumer culture, and ‘good’ design was all about creating objectively beautiful, functional items within that confident, progressive world. But as the 1960s turned into the 1970s, things began to change. Economies ceased booming, radical countercultural movements in music, fashion and art came to dominate the mainstream, and social and class boundaries became increasingly complex and hard to define. Binary modernist ideas of ‘good’ and ‘bad’ taste, ‘bel design’ or ‘kitsch’, ‘high’ or ‘low’ culture seemed too simplistic. Inevitably, architects, artists and designers reacted. And, as ever, table lamps provide perfect illustrations of how the new ideas manifested themselves...

Anti-Design

'Cespuglio' table lamp (1968) by Ennio Lucini.

The first overtly counter-modernist design movement began in Italy in around 1966. Despite its name, the ‘Anti-Design’ school was not, of course, opposed to design. Indeed, it placed the designer in a new position of importance, elevating the creator’s imagination above function, aesthetic rules and the needs of mass production. Rejecting ‘form follows function’ and any idea of ‘good’ design, Anti-Design exponents like Ettore Sottsass, Ennio Lucini and, in Britain, George Sowden played around with garish colour, awkward shapes and deliberately distorted scale. They made objects that were expressive, elaborate, kitsch occasionally pretty impractical and sometimes outright ugly. Anti-Designers valued uniqueness, not the uniform perfection of the factory production line. As a consequence, styles varied wildly, as these examples show:

The Pistillo lamp was designed by Studio Tetrarch in 1968 and produced in Italy by Valenti. Based on the inner parts of a flower, it could be used as a table, ceiling or wall light. Image credit.

'Star lamp' (1972) by George Sowden. Image credit.

Pop art and design

Bulb Table Lamp by Ingo Maurer for Studio M (1966). Image credit.

Another strand in the Anti-Design movement was the response to American pop culture and to the Pop Art of Andy Warhol and Roy Lichenstein, which imported the imagery of mass consumerism - whether soup cans or movie stars – into gallery art, and deliberately blurred the boundaries of high art and popular culture. Furniture and lighting designers brought the bright, ‘cheap’ plastics from the American diner into the home and used irony and humour to make bold, surprising statements.

'Pillola' table/floor lights (1968) by Cesare Casati and Emanuele Ponzio. Image credit.

Studio Alchimia and The Memphis group

'Valigia' ('Suitcase') table light (1977) by the key postmodernist Italian designer Ettore Sottsass. Image credit.

Believe it or not, ‘postmodernism’ as a term first appeared way back in the 19th Century, but it wasn’t until the 1980s that it was applied to architecture and subsequently to design. A postmodern building does more than offer form or function: it seeks to ‘speak’ to its observers, using irony and humour and stylistic historical references or ‘quotations’. At the beginning of the 1980s the most cutting-edge contemporary design collective in the world was the Milan-based Studio Alchimia, which developed a complete postmodern theoretical approach in direct opposition to functionalism. Influences by the Anti-Design and Pop movements, the objects it released in the Bauhaus and I Mobili infiniti collections were wholly unlike anything in modernism, deliberately throwing together discordant shapes and colours in weird furniture ‘collages’.

The anti-functionalist (indeed, practically useless 'Sinerpica' table lamp (1978) by Michele de Lucchi. Image credit.

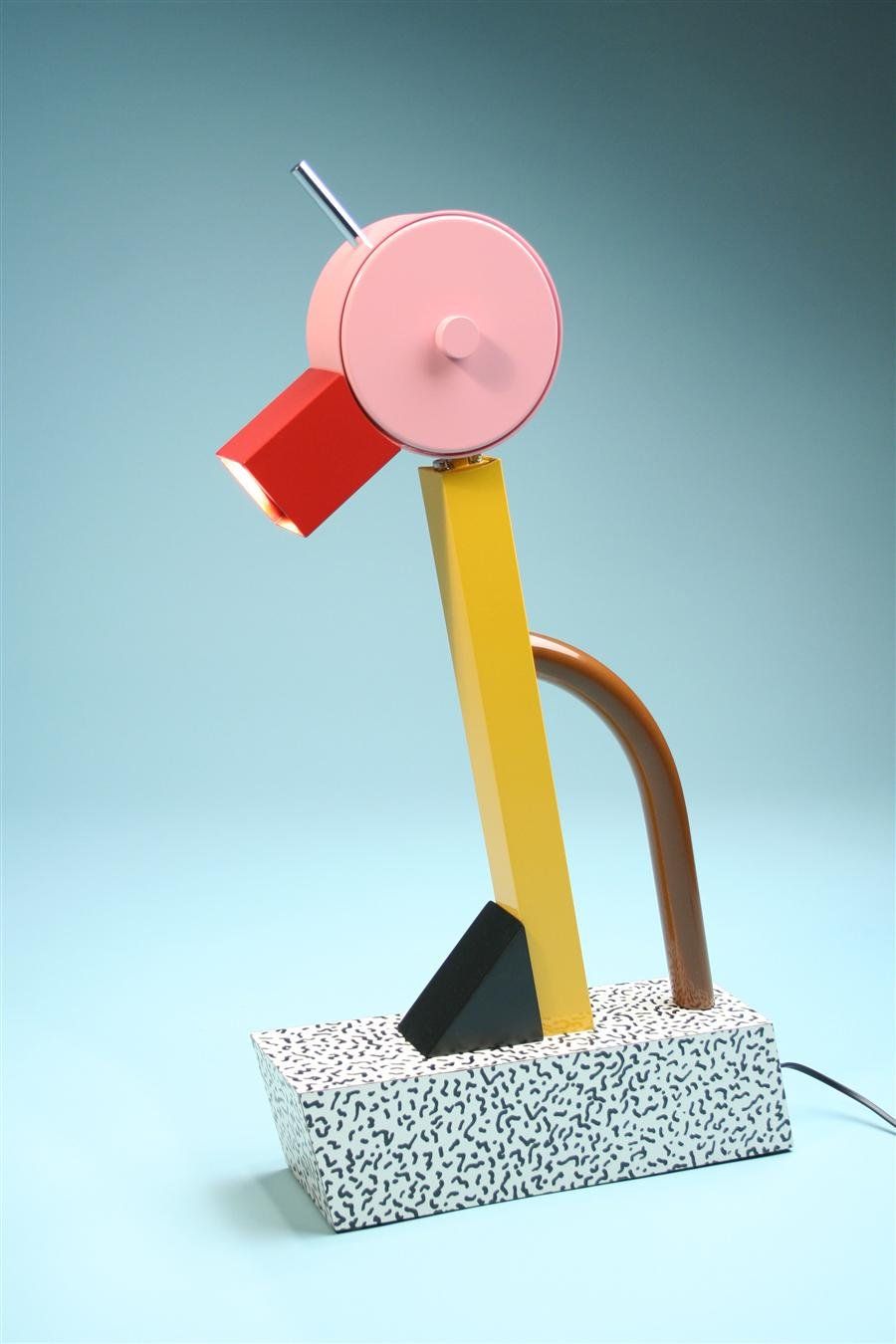

In 1981 several of the key designers from the Alchimia studio, including Ettore Sottsass and Michele de Lucchi left to form a new group, which they called Memphis. Memphis became the postmodernist powerhouse in domestic design through the 1980s. Their theory was to completely abandon worries about practical purpose and create a form of ‘communication’ with the users, by making playful objects influenced by things from everyday life: toys, movies, comic strips, fast food restaurants.

'Super lamp' (1981) by Martine Bedin - a postmodern classic evoking traditional toys. Image credit.

Sottsass, the leading light of the Memphis studio, was at various times anti pretty much everything: anti-consumerism, anti-taste, anti-fashion, even anti-posterity. ‘We are sure that Memphis furniture will soon go out of style’, he pronounced. Nonetheless, the Memphis philosophy spread to every part of the design world.

'Tahiti' table light (1981) by Ettore Sottsas under the Memphis studio name. A deliberately 'anti-good taste' lamp. Image credit.

The New Design

The immediate legacy of Memphis and the postmodernists was the New Design movement of the 1980s and 1990s, which had distinctive forms in Germany, Spain, France and Britain.

'Aerial light' (1982) - a salvaged metal lamp by British 'New Design' exponent Ron Arad. Image credit. In London, designers like Ron Arad and Tom Dixon found a new simplicity, and used rough materials – salvaged metals and recycled objects – to make one-off items. In France, the New Design took wildly different turns, from the shock factor of Jean-Paul Gaultier in fashion to the elegance of Marie-Christine Dorner’s interiors. In French furniture and domestic appliance design, the big star to emerge was Philippe Starck. Working in a variety of materials, Starck took a broadly postmodernist aesthetic, with striking, individualistic and organic forms - but designed for mass production and affordability (think the iconic Juicy Salif lemon squeezer). So in many ways he has less in common with the Memphis school than he does with the great Art Nouveau designers, featured way back in part one of this series.

'Miss Sissi' table lamp (1990) by Phillippe Starck. Image credit.

Post-postmodernism?

From the exquisite art nouveau glass designs of Émile Gallé and Louis Comfort Tiffany to the most unsettling postmodernist lights, every step of the journey of 20th century design can be seen in the changing looks of table lamps. But where are we now? Perhaps ‘post-postmodernism’ is indeed the best description of the world we now inhabit. We have accepted the postmodernist idea that there is not really any such thing as objectively ‘good’ or ‘bad’ form. Designers are free from the rules laid down by the modernists of the early 20th Century, but now they are also free from any need to react against those rules, meaning they can follow them if they wish. Today, the modernist idea that there is an ideal design for a mass-produced object which is right for an imaginary theoretical ‘consumer’ seems absurd. Rather, the power to select objects for their aesthetic qualities lies with the individual, who has more choice than ever before. You can decorate and furnish your homes in broad aesthetic styles – from industrial to minimalist to shabby chic to retro – or mix and match to make a completely unique look of your own.

Pooky's 'post-postmodern' Lucas table lamp in red and orange resin.

So we like to think that the Pooky range of designer table lamps is a perfect example of the way that domestic design has evolved. Our lights have been influenced by more than a century of innovation by great designers, but in the end, only one person now decides what constitutes a great table lamp design: the person who buys it. The History of Design in Table Lamps series: Part 1: Thomas Edison to Art Nouveau Part 2: The Birth of Modernism Part 3: Art Deco Part 4: Midcentury Modernism